Bodley’s Court, King’s College Cambridge, from Wikipedia. Turing had rooms at the top of the corner by the river, I think for the academic year 1947-1948, so Annan would have been in the rooms below. Fellows of King’s are for the most part University teachers who also teach for the College, and offices like these are a considerable perk of Fellowship. I imagine Turing’s old rooms are particularly highly sought after. But there is one Fellow whom I heard say around 2000 that he was pleased not to have Turing’s, because he felt uncomfortable about occupying the rooms of a suicidal homosexual.

I read this account of Alan Turing ages ago and then forgot all about it. I tried to avoid putting too much Cambridge into my Manchester story, important though it is to the story (& frankly, to me). But if I had remembered to put this southern view of Turing in I would have done. It’s from Noel Annan’s entertaining insider account of the twentieth century academic establishment, Our Age:

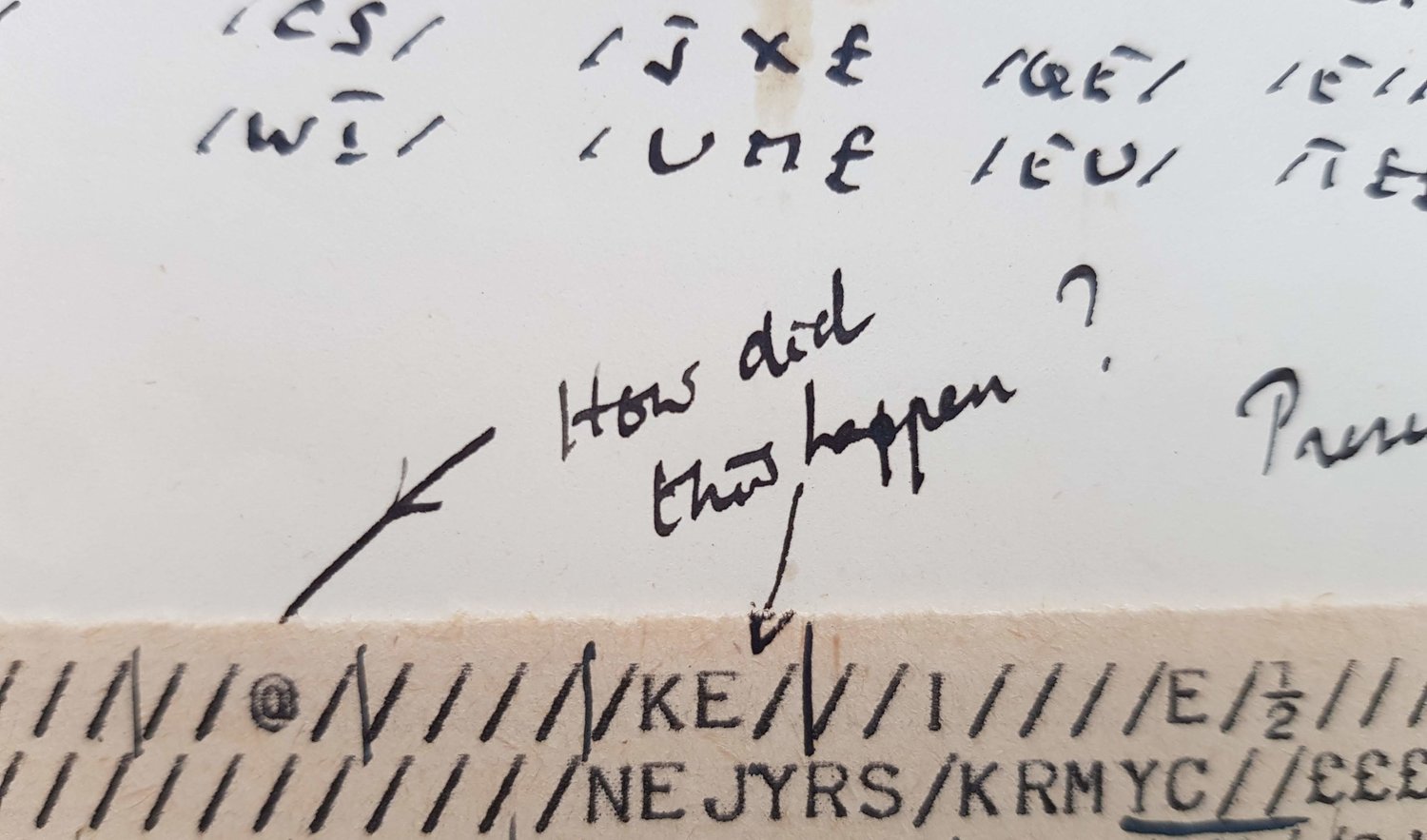

It so happened that when I returned to King's after the war I had rooms beneath Turing, both of us living as bachelors, and he helped me to understand what some of the great mathematicians were at whom I was studying as I worked on the history of ideas. I liked his sly, secret humour. Turing was all that the journalist spy-hunters hated most. His inner life was more real to him than actuality. He disliked authority wherever he was...sceptical of politic and schemes for reforming the world, he was not likely to be elected to the Apostles in its Marxist days. But then he was not a typical public school rebel. He was a cross-country runner of international stature and enjoyed games and treasure hunts and silliness. He poked fun at conventional people, enjoyed teasing the humanists by arguing that thought was made up of inputs and outputs and of storage capacity. If a machine could solve problems, could it not also think? Could it not think? Could it not write a sonnet? (Leavis exploded.)

Turing was the purest type of homosexual longing for affection and love that lasted. He was so remote from the wisdom of the streets that when he was a professor at Manchester, where he had found a working-class lover, he went straight to the police when the boy stole some of his things. They were astonished that Turing showed no sign of shame and thought he had done the right thing to expose dishonesty and the betrayal of trust that goes with love. The laws of his country which he had served so well closed in on him. He was sentenced to psychiatric treatment, given hormones and to his disgust grew breasts. He killed himself. Stephen Toulmin saw him as the product and victim of his social class: it gave him the freedom to be eccentric but destroyed him when he ignored the conventions. But there was one convention which he and the sloppy free-wheeling community of intellectuals at Bletchley did not forget. They did not betray their obligation not to reveal what they had been doing and kept their secret for thirty years after the war.

(One of the ways in which Annan is entertaining is his recurrent inability not to have a dig at FR Leavis.) Annan’s judgements are his own, but after the first two sentences, with that report of the sly, secret humour, he actually gets all his facts from a 1980s review by Stephen Toulmin of Andrew Hodges book: Turing was not central to the post-war world view from King’s College and I doubt Annan was getting news on Alan Turing’s in Manchester at the time.

More useful evidence, though, comes when Annan reports on the men at the Home Office who were consciously implementing newly repressive anti-homosexual state action at the time. On David Maxwell-Fyfe,

a Scot on the make at Oxford, he had learnt that the way up in Chamberlain's circle was through undeviating rectitude, and he continued to display rectitude when made Home Secretary. His permanent secretary was Frank Newman, an handsome womaniser and reactionary - an English Pobedonostsev.

Annan also attributed the rise in convictions to the appointment of the Theobald Matthew, a Roman Catholic, to the position of Director of Public Prosecutions in 1944 after the lawlessness of the war:

...like the prefects of a slack house at a public school these three, aided by a new commissioner of police, determined to pull the place together: and they had a pretext.

The title is a nod to the wise spider of Akan folklore. Noel Annan’s Our Age was published in 1990.