[Updated May and June 2025 with more material, some found and generously shared with me by Mark Priestley]

Bernardo Gonçalves has a nice new paper out on the Turing Test, partly making use of a couple of letters to Beatrice Worsley in the Smithsonian archive. I don’t have much to add to Bernardo’s paper, but this source does help me illustrate that Turing had a major blind-spot: he didn’t generally take women seriously as mathematicians. Worsley is notable as the only female mathematical thinker for whom there’s any evidence of any intellectual traffic with Turing. (According to Hollywood, Joan Clarke achieved the same respect, but there’s little evidence for that beyond the desire to see Turing as a sympathetic figure.) In this of course he was hardly alone in this among his professional male peers: see this contemporary US report about how his mentor Max Newman was a superb manager at Bletchley Park save for the fact he didn’t make good use of female talent.

In 1950, Turing was committed to the idea of using the new electronic computers to do thinking with using mathematical logic. That - rather than building a fast calculator - was why Max Newman had succumbed to Patrick Blackett’s enticement move to coal-black Manchester, over the objections of his wife Lyn, and why Max had in turn recruited Turing there in 1948. But Newman never did any active research on the computer and Turing was left, intellectually, entirely on his own. As the engineers took control, the project of doing research in mathematical logic on the new electronic computers was running into the ground while mathematical resources went, instead, into numerical calculations.

There were two young, enthusiastic and First-class mathematically trained women Turing could have used to build a research group around. Audrey Bates and Cicely Popplewell shared Turing’s office, and indeed Audrey Bates’s first job was to implement a version of ‘lambda-calculus’ - the tool of choice of mathematical logicians on the Manchester computer. Right from the beginning though, Popplewell’s role was as a systems programmer, and as soon as her MSc was finished, Bates too moved into a similar role. It can hardly have helped her lack of engagement with Turing’s intellectual program that Turing barely thought she and Popplewell had a right to exist, as one of the two once told Andrew Hodges.

But the archive does show one young woman that Turing was prepared to engage with. In the autumn of 1950, Beatrice Worsley, a Canadian who had started a PhD the previous year in Cambridge, where the rival EDSAC electronic computer of Maurice Wilkes, was already operational, came to Manchester for a few months and she and Turing later exchanged several letters, his perhaps a little patronising, over the mathemtical logic projects.

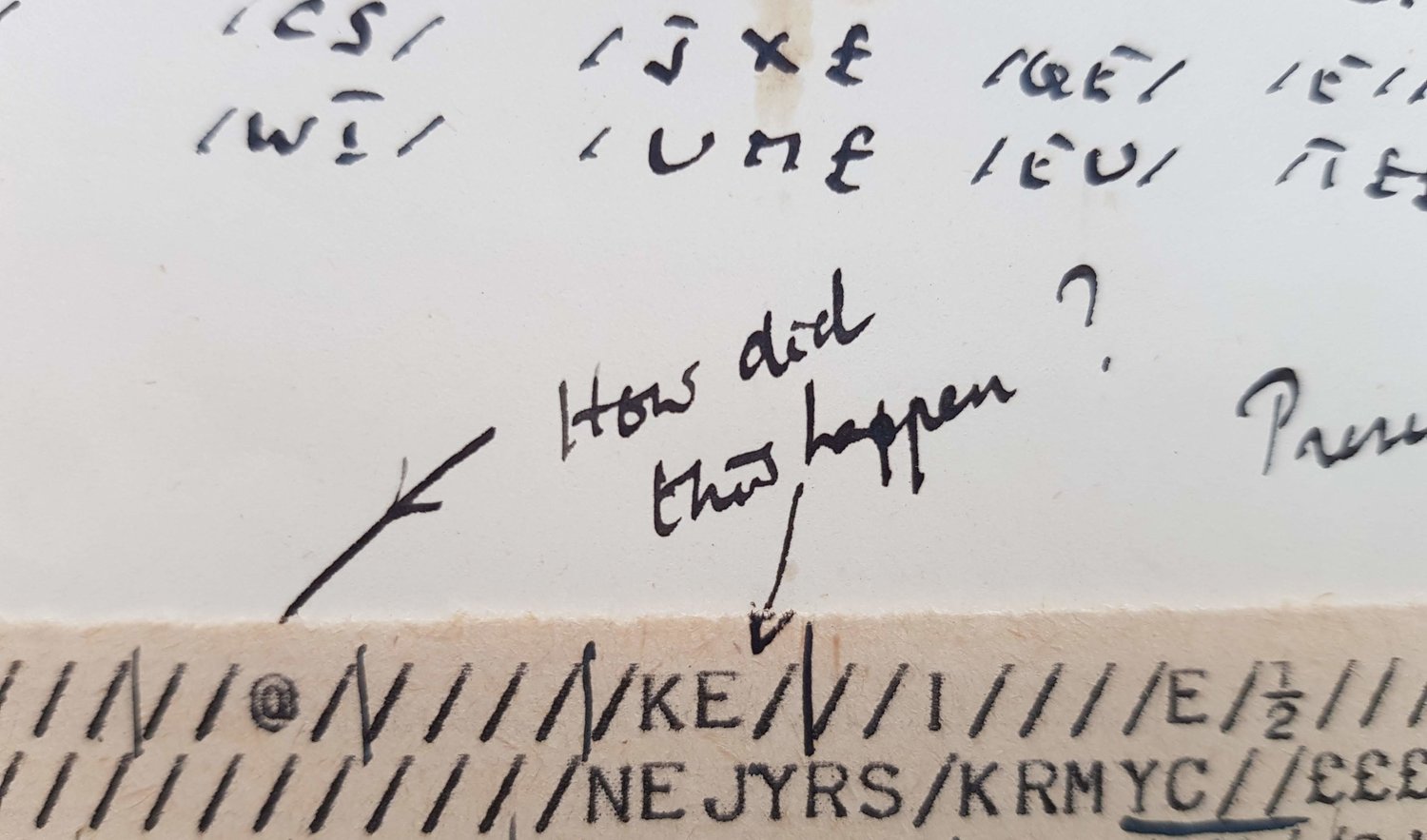

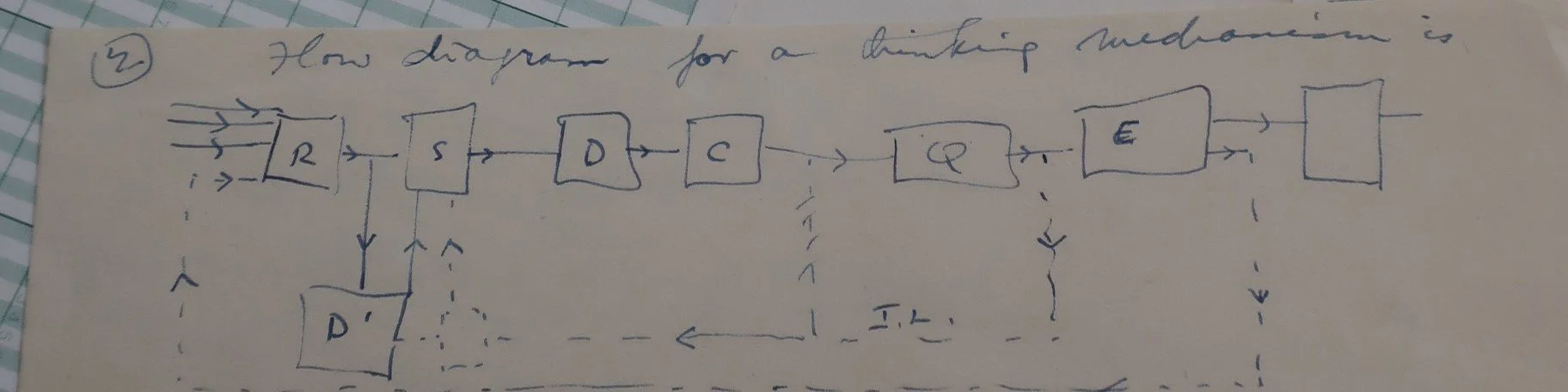

So how did Worsley establish this right to exist? Perhaps she came to Manchester because she was interested in Turing. It is not impossible that Worsley was one of the few people around who were interested in Turing’s main preoccupation in applied mathematics at the time, the generation of biological form. Whilst in Cambridge she took and (tellingly) preserved some intriguing notes on a talk she later labelled as a ‘physiology colloquium - Univ of Cambridge 1949’ that discussed a number of issues that were occupying Turing at the time. There are references to information theory, and to the Rashevsky house journal from Chicago, the Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, and one diagram headed ‘flow diagram for a thinking mechanism’. (The five relevant sheets are displayed in the gallery nearby: these papers are in the National Museum of American History Worsley papers Box 1 Folder 1).

It’s unclear who the speaker was; I’d say not Turing, but the notes have a Ratio-y Club feel. Perhaps Woodger or McCulloch, but I can’t find any trace of them in Cambridge at the time. It’s possible that the 1949 date, which was added later by Worsley, is a misremembering, which widens the possibilities. (One other name that I wonder about is Anthony Oettinger but I don’t know enough about him).

Whilst in the archive I also saw this comment by Wilkes which is an interesting gloss on Women at the console. ]

…the reason for requiring automatic sequence operations is … to get, in effect, an operator who will work for 168 hours a week without tiring, and can be trusted to do as she is told without making mistakes. Maurice Wilkes’ 1947 justification to the Universit of Cambridge for building the EDSAC electronic computer: Cambridge University Library UA/COMP 1/2.

Worsley’s time in the UK was in part difficult, but there’s no conclusive explanation of why. The most substantial (indeed the only) biographical article on Worsley says that

Worsley started writing her dissertation at Cambridge, but in 1951 for some unknown reason she returned to Canada with the text unfinished. She arranged to complete the work with the supervision of Byron A. Griffith, a professor of Mathematics at the University of Toronto and a member of the Computation Centre. Worsley wrapped up the writing quickly and was rehired as a staff mathematician at was rehired as a staff mathematician at the Centre in July 1951. Hartree approved the dissertation in Cambridge, and Worsley’s doctorate was awarded in 1952 after Hartree made a visit to Toronto. (Cambell, 2003)

The Cambridge files show (UA/BOGS/1953/Worsley) that just as Worsley was finishing an MSc on ‘Computing Machines’ at MIT, in May 1947, she applied to work on the ‘design and contruction of new machines and investigations into their mathematical capabilities’. Wilkes replied to say, not unwisely that ‘it would have to be clear that during the first two years most of the work would be of a practical nature in getting the machine to work. And in due course Worsley arrived in October 1948 as a graduate student at Newnham College. She lived in Whitstead, a hostel exclusively for Newnham’s foreign graduate students, round the corner in Barton Road, in what seems to have been a small and mainly supportive small community, at least according to the majority of memories in a small booklet still in Newnham, Memories of Whitstead. Intriguingly, Worsley is remembered in those pages as a keen photographer at the time: it would be fascinating if any of her photographs have survived anywhere. (The same volume also includes a slightly later, but all-too-imaginable word portrait of Ted Hughes persistently happening to come round to use the hot bath in the all-women hostel and wandering from there to Sylvia Plath’s room in a state of some steamily masculine undress).

There is no hint of any particular problem in the Cambridge files. By the end of the academic year, in Junr 1949, Worsley was one the one trusted to write-up an account of using the EDSAC for the proceedings of a Cambridge conference. At around the same time she was, as was normal practice, retrospectively registered for the PhD; it was a little over a year later, on 19 Sep 1950, that she wrote to the University saying that both Wilkes and she felt that ‘the third year at work with another machine to the EDSAC would be very beneficial for my thesis and my future career’ (COMP 6/1). It is plausible that these words can be taken at face value; perhaps it was simply Wilkes sticking to his original plan and both of them recognising that Newman and Turing, rather than Wilkes were the people to work with for ‘investigations into mathematical capabilities’ of computers. It was unlikely to have been a fleeing from Cambridge misogyny; there is evidence that Hartree, the professor in Cambridge, was much more sympathetic to female graduate students than there was any sign of in Manchester.

A letter of December 1950 from Worsley to Turing, now in the University of Manchester (in the Special Collections TUR/Add 13 and 91), does indeed says that she intended to return to Canada because of medical advice to ‘take a prolonged change from academic work’. That might be why, in September 1952, she was listed as on the local program committee of the Toronto ACM meeting but did not make any other mark on the Proceedings. But the correspondence with Turing continued and confirms that by 1952 she was actively thinking again. It included practical career matters and applied mathematical issues, but also, notably, Worsley’s ambition to find the simplest program which would ‘provide the functions necessary for the calculation of a computable number consistent with your theory’. This seems to have been intended to end up as a chapter in her Cambridge PhD thesis, which she was eventually awarded at a distance, without an oral exam, in January 1953. The BOGS files reveal that this was a borderline decision: Hartree voted for it, but the external examiner JH Wilkinson voted against and it was only the casting vote of Wilkes himself, plus Worsley taking a written exam at a distance, that finally swung the day.

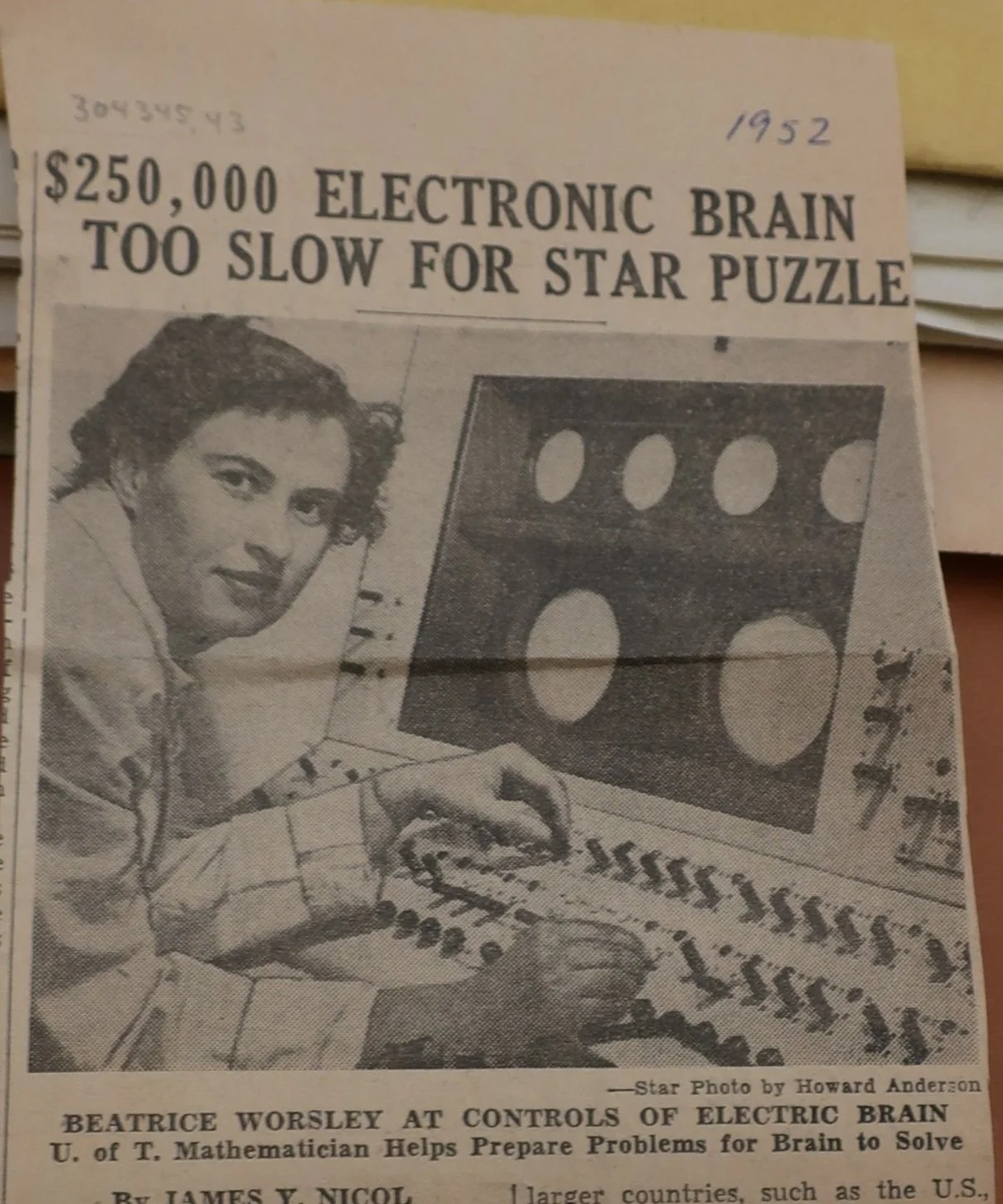

Beatrice Worsley in the Toronto Star, 1952, helping to 'prepare problems for Brain to Solve'. (The star puzzle was a newspaper circulation gimmick, not a cosmological model).

Worsley’s inner life remains pretty opaque beyond an enquiring mathematical brain. As far as the world knew, she never had any romantic partners, and all we know about her family life is that she barely spoke to her sister-in-law. One of the few glimpses was noted in Scott Campbell’s 2003 biography: at Worsley’s death in 1971 she left her decent sized estate not to her living siblings but to the University of Cambridge she had left in a hurry twenty years earlier. (Worsley died of a heart attack at the age of 50 so this one might speculate this Will was one made much earlier.) Moreover this was specifically to found a ‘Helge Lundgren’ studentship. In 2003 Campbell didn’t know who Lundgren was so by implication the sister-in-law either wasn’t telling or didn’t know, but it seems likely to me that this was in memory or honour to the Helge Lundgren who was a prominent Danish canal engineer. A romantic speculation might link that to the flight from Cambridge, but is very unlikely. The likeliest time for any personal connection with Lundgren was after the Cambridge years, as the the major application for the Toronto computer, Ferut, was simulation of the hydraulic behaviour of the St Lawrence Seaway, Beyond that, there’s not much.

Bernardo uses Turing’s letters to Worsley of 1951, now in Washington, to good effect in explaining Turing’s opinion of his Test, but to see an early reception of these ideas it is the letters in Manchester (which run through 1952) that show how Worsley responded with her own ideas:

In connection with your paper on computing machinery and intelligence I'm still trying to think of some property of the human mind which could not be duplicated by The Imitation Game. I feel intuitively that if there is one it must be in the direction of spontaneity. McCulloch and Pitts in an article in the Bulletin of Mathematical Physics postulate a brain mechanism in which the threshold of excitement of the neuron can be determined by the neuron itself.

It’s not a ground-breaking response but it is an engaged one, and as such rather unusual among mathematicians of the time.

Thanks to Jonathan Dawes for investigating the SSEB proceedings and identifying the 1949 meeting. For the Ratio Club, I have taken my view from Husbands and Hollands 2008 article. At more length I have only just read Andrew Pickering’s superb book, both readable and indigestible, The cybernetic brain: sketches of another future. The day this was first posted, Colin Williams, who I had a great drink with in the pub once in Oxford, has shared with me for the first time his completed PhD on British cybernetics, which claims to be ‘archivally rich and methodologically innovative’, and changing ‘our understanding of post-war British history so that’s something to look forward to reading properly. One superficial response: I don’t think I’d agree with Colin’s claim that Pickering’s book was merely in the service of sociological intervention; it is packed with vivid and well sourced history.

[Update Dec 2025 with the Toronto and Cambridge proceedings. The 1949 Cambridge meeting was the Conference on High Speed Automatic Calculating-Machines, 22-25 June 1949; the proceedings don’t seem to have made it into any UK libraries as a book but there are copies in several manuscript collections including NAHC/EDS in Manchester and, thanks to Simon Lavington, in the Science Museum LAV. (I recall reading it once in the Gates building in Cambridge but can’t locate that again). Intriguingly one other attendee was a Miss R. B. Bonham-Carter, who is is easily found in a group photograph showing her a member of the Cambridge EDSAC team, but is otherwise invisible to Google.]