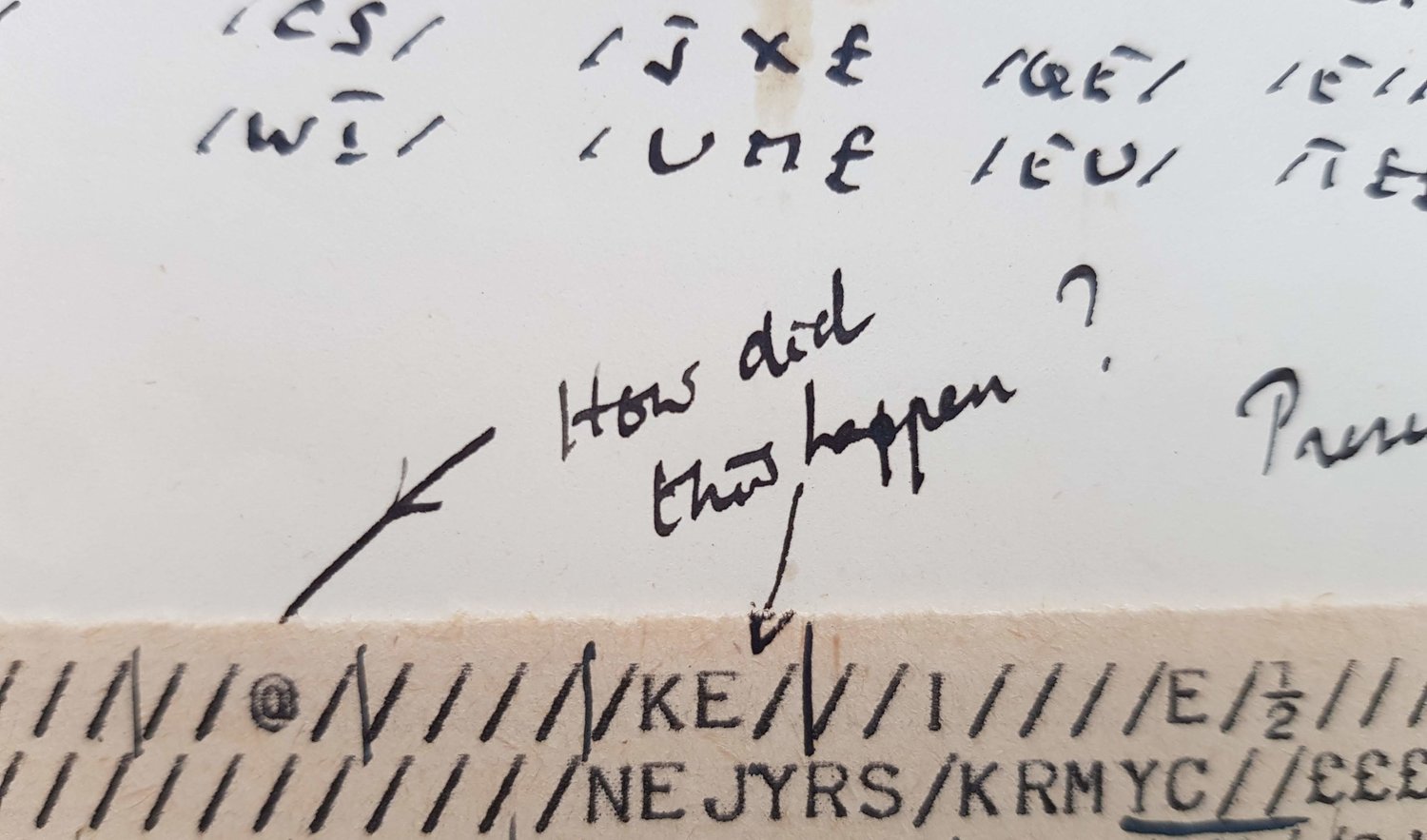

A map of the central Manchester University precincts around 1950. The four brown regions are, top to bottom,

the ‘lavatorial’ room where Williams and Kilburn’s 1948 ‘Baby’ prototyped the earliest practicable electronic memory bits, and in the process generated a plausible claim to run the worlds first computer programme.

the 1950/51 (?) Computing Laboratory, partly built with Max Newman’s £35000 Royal Society grant and the ‘little steel’ he extracted from a reluctant Ministry of (war) Supply. This housed both the successor to the Baby, the Manchester Mark I and its human labourers including individual offices for both Kilburn and Turing.

The offices of the mathematics Professor, on the top floor of the original Waterhouse lecture building

A lecture room in the Arts Building, possibly the site of the 1950 discussion on ‘Mind and the Computing Machine’ that seems to have provoked Turing into writing his Mind paper introducing the Turing Test.

None of these interiors are open to the public, though all can be clearly seen from public spaces. The University has in the past run walking tours that offer access, though they may have lapsed at the same time as the post of University Historian.

I post this partly because a publisher’s error has corrupted the map in the second printing of the book.

I drew this map and it specifically is freely copiable under a CC-BY copyright license (in fact I am happy to share the Adobe Illustrator files if you want to add anything). It is partly based on a 1926 booklet, The Victoria University of Manchester: a short historical and descriptive account; there is a copy of this in Universty of Manchester Special Collections. Aspects are mildly speculative, I should perhaps add offices for a (human) pre-war computer in the basement of the Christie Building and the wartime location of Hartree’s differential analyser in the basement of the 1909 Physics building. (It also seems a bit odd not to mention that building is where the atom got split.) Further references are in the book. The buildings south of Burlington Street have largely now disappeared.