Institutional memory in of Turing in King’s College (about which I have written here) tends, not wrongly, to point to a rather nice set of rooms by the river as ‘Turing’s room’ and I thought it was finally time to check.

True, for Alan Turing by Antony Gormley, with information plinth (critique? homage?) by King’s College Entrepreneurship Laboratory. It was revisiting King’s to watch the unveiling of this sculpture which prompted me to reflect on Turing’s bed and bath…

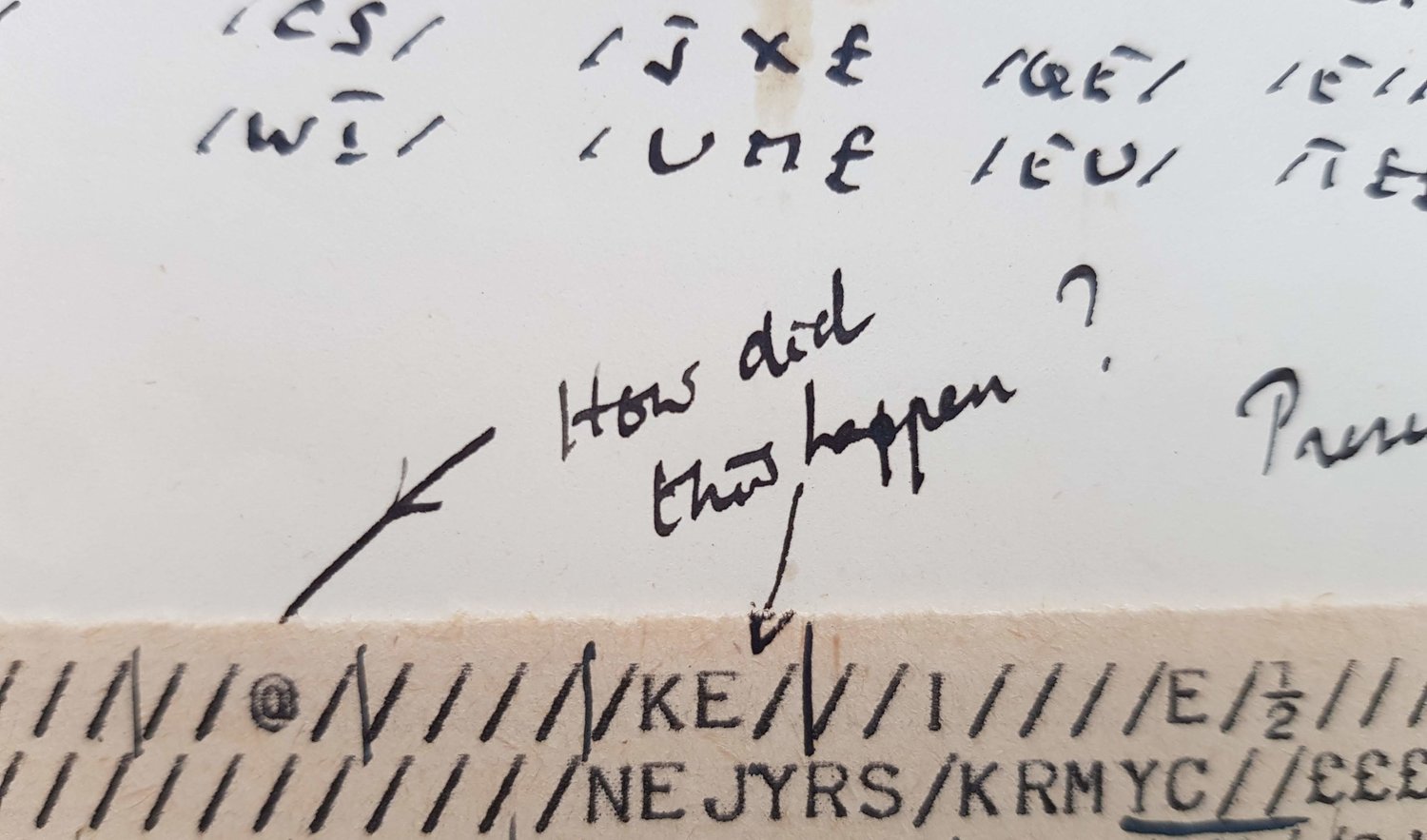

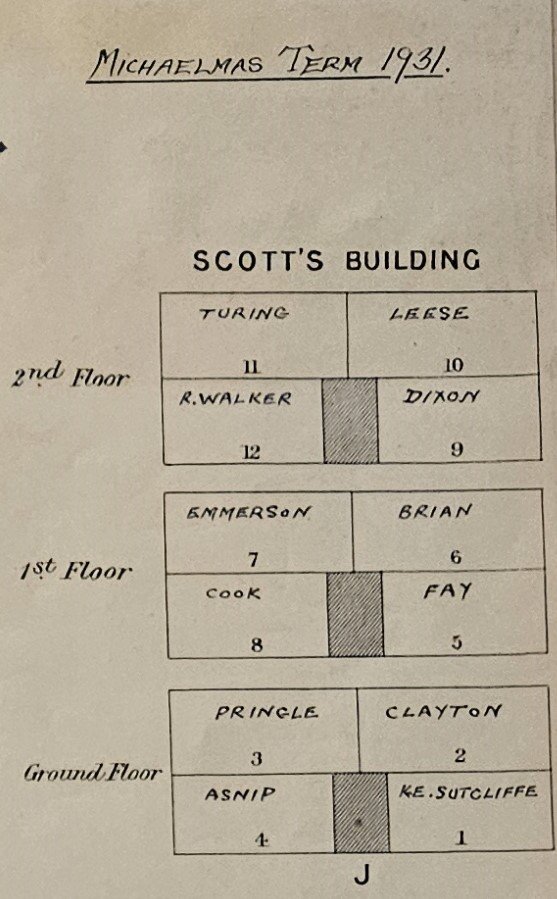

Turing’s first year room in the 1931 plans preserved in the Archive Centre, King’s College, Cambridge, KCAC/1/3/2/1.

The archive research, then: The College still hold schematic room allocations from the period. In his first year at King’s in 1931/1932, Turing had rooms in J.11 at the top of the Scott Building; in his second year on the ground floor of Webb’s Court in Q.2, and in his final undergraduate year he moved into S.8 at the top of S staircase in Bodley’s Court, paying a termly rent of £9 5’. He stayed there in the following year as a graduate student before winning his Fellowship in 1935 and moving into rent-free rooms in X.8, also on the top floor but with windows opening onto a view of the Cam. The floor plan records stop in 1938, but chances are Turing was re-assigned this room upon his return from Princeton in August 1938 until he finally relinquished his Fellowship in the spring of 1947; he went on visiting Cambridge for long periods from then until his death in 1954 and it is unclear where he stayed when he did but very strong chances are it was a room in King’s.

The title of this post was briefly ‘I had sex in Alan Turing’s bedroom’ as I had first thought that the 20 year old Jonathan Swinton had spent a year in what had once been the bedroom of Q.2, and that Turing’s ghost would have encountered my coming to terms with the physical realities of two bodies in one single bed. After a bit I borrowed a double mattress off someone; I vividly recall four of us carrying it across King’s Parade in something of a visible challenge to the don’t-ask-don’t-tell attitude to extramural overnight visitors then prevalent. But I was wrong (about Q.2: the mattress definitely worked) as I had miscalculated how the rooms were renumbered in the 1950s when the sets of sitting-room and bedroom had been split into two separate bedrooms to double the accommodation for students. So I didn’t ever sleep in Turing’s bed in Q.2, alone or not. (In any case, the college didn’t provide furniture in Turing’s time: students had to rent or buy their own, often from the previous occupant) But Turing’s first year room, J.11, I now realise from seeing the maps, was later converted into what was my shared bathroom in my final year. And the bath was huge. And the water was boiling hot and I could lie in that bath for hours and hours and I did, instead of revising. Unfortunately Turing’s ghost was no good at helping me out with my finals, which I hated and did very much worse in than Turing’s extremely good First.

Please don’t be tempted to try and take a bath in any of these rooms yourself: they still function as student and staff accommodation and even if you can conquer both the locked doors and your own respect for privacy half of them have changed numbering anyway, so you wouldn’t even be seeing the correct shrine. And making a pilgrimage to a shrine won’t get you a First any more than it did me.

Some slightly more historically relevant observations on these room allocations. Firstly, in the language which often introduces elite male friendships of the time, Turing ‘shared a staircase’ in that impressionable first year with, among others, the zoologist JWS Pringle. Pringle went on to be a significant zoologist who was one of Turing’s post war links with the Ratio Club, and perhaps more significantly for his thinking on morphogenesis, with the Society for Experimental Biology. (As an aside, I’ve just recently noticed this oral history which if accurate pushes back the date when Turing talking in public about morphogenesis to the first British Mathematics Colloquium in the summer of 1949. It would be great if a printed programme for that emerged). Also on that staircase was the grammar school boy Fred Clayton, who would become a significant friend, although Hodges asserts this wasn’t until their third year.

The room plans, which are far from forgotten and do come out on show regularly, are potentially quite interesting for the (relative) social gradations on display. There was a set of rather dark and dank buildings on the other side of King’s Lane, swept away in the 1970s, and the plans show that the rents for these were slightly cheaper at £8 a term rather than £9 for the rather nice sets in Bodley’s or the very grand (but austere and bath-less) staircases in the Gibbs building at £10. I wonder if there’s a correlation between the desirability of the rooms and the perceived prestige of the occupants. King’s in the 1930s had for decades been taking more than Etonians but it would be interesting to see where they, or students who had done well in the entrance examination, were placed spatially: in particular I wonder if they were the only ones allowed to live in the Gibbs building. That prestige space has now long been reserved only for Fellows. I’ve also sometimes wondered why Keynes had rooms in the (currently) less valued Webb’s Court development of 1909; perhaps he thought they were more contemporary and stylish than Gibbs, or perhaps he liked the fact there were toilets (in the basement). He was a vigorously modern man, though I bet he only had a single mattress.