An interesting little fragment from the Keynes archive on King’s view of itself and of Turing, in 1939. The context is a debate between two King’s dons discussing the problem of what to do with the College’s young Research Fellows as they came towards the end of their Fellowships. The business model of the College rested on earning undergraduate tutorial fees, and there was no significant equivalent of modern external PhD funding. A surplus from the College’s endowment, which was incorrectly believed - then and now - to have come from Keynes’ magical money powers, was used to support young men as Research Fellows at the start of research careers. The older man, economic historian John Clapham wrote

Image by permission of King’s College Cambridge.

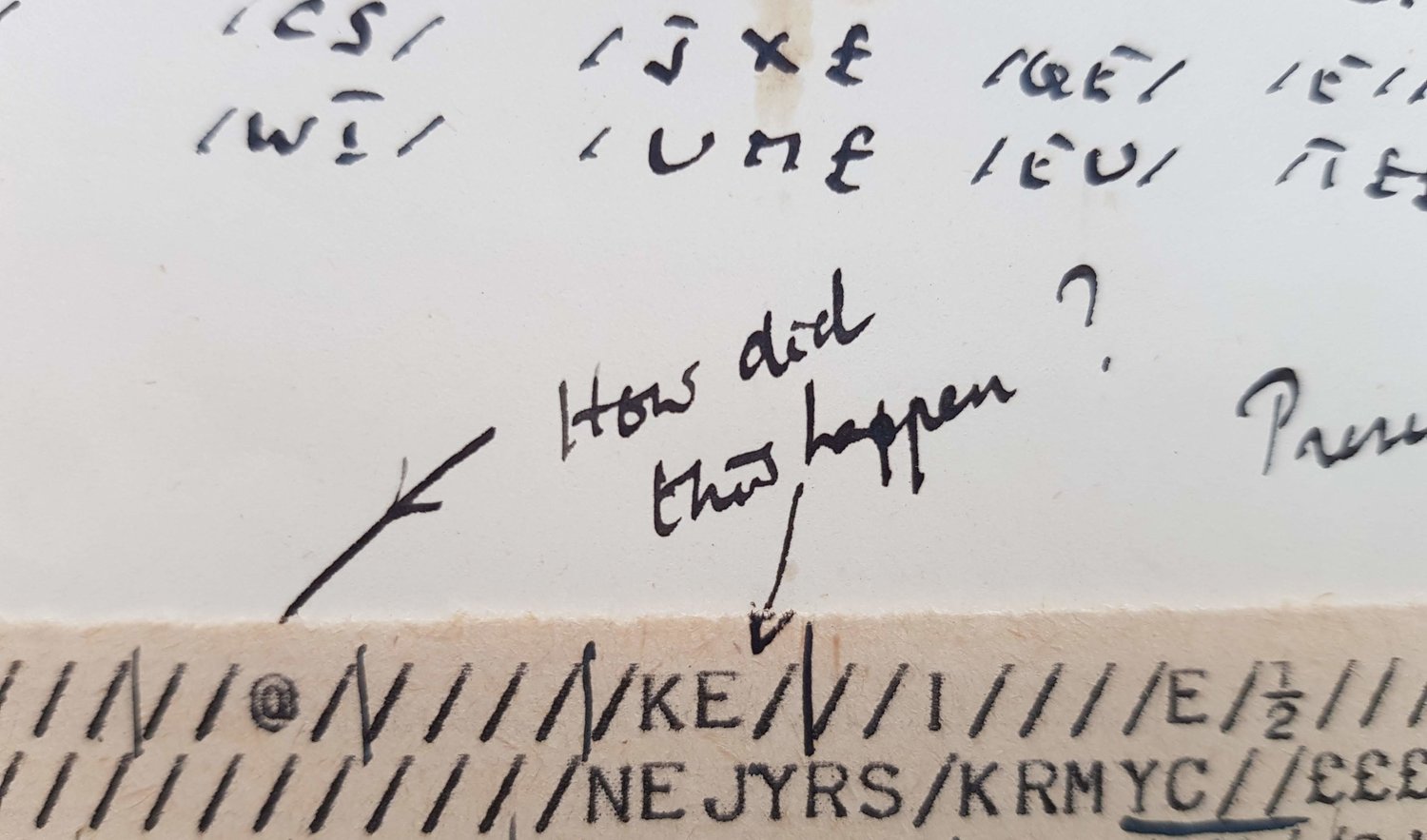

One of the 6 [non-permanent King’s Fellows] is Turing, a most brilliant fellow I should like to see kept in Cambridge, for Cambridge’s sake if not his. As our mathematical staff is overfull his proper destiny is the staff of another College. Several are weak in mathematics… [22 May 1939; Keynes KC/2/384]

In a similarly polite and collegiate reply - although I sense an underlying tension in the correspondence - the younger and more worldly Keynes responded that he had

a little doubt as to whether we have been strict enough in the past’ [about terminating Fellowships] ‘the average quality is by no means bad; it is the comparative lack of outstanding figures which is so striking. The prospect of going on with substantially the current staff … is death to the College’. The real test case on your list, because it will come to a head fairly soon, is to my mind Turing. If another College elects him to a Fellowship, well and good. But if not I would consider it absolutely disgraceful if we should drop him after six years, and we should take the earliest opportunity of giving him some small emolument beyond his Fellowship. He is, in your words, ‘a most brilliant Fellow’…if the expert reports on him turn out to be what I and I gather you expect them to be, I would feel a blight had fallen on our prospects if we were to drop him. [23 May 1939; Keynes KC/2/389]

Clapham in turn responded

Turing I am quite prepared to consider under the nine-year rule. I am not at present prepared to put him on the Tutorial Fund (unless for next year in Ingham’s absence; in which case of course I would).. I am prepared to carry on men of the Turing stamp now and then. [25 May 1939; Keynes KC/2/397].

Turing certainly had made a brilliant contribution with his 1936 paper on computable numbers, but neither Clapham nor Keynes were in a position to judge its value in a then small field of mathematical logic thought to have no practical application. (It would have helped, though, that there was a lineage from GE Moore and Bertrand Russell.) I wonder who the experts were who persuaded Clapham that Turing was a ‘most brilliant fellow’. My guess would be a Cambridge mathematician capable of impressing a historian with the civilised nature of their High Table conversation, so probably it wasMax Newman. But it’s odd that Keynes seemed to be expecting ‘expert reports’ on Turing in May 1939. I wonder if Turing was being tested out, with or without his knowledge, for a university promotion to a permanent job at the time. Four months later, of course, Turing reported for duty at Bletchley Park and everything changed. When he returned to King’s in 1947 to take up the final year of his Fellowship both Keynes and Clapham were dead, and there is no record of whether anyone still wanted to carry on with ‘men of the Turing stamp’. Whatever King’s or the ‘weak in mathematics’ colleges thought, Turing left for Manchester and for good at the end of the year.

There is a caricature of post-First World War King’s as populated by elderly dons desperately trying to re-elect young men as beautiful and brilliant as Rupert Brooke into vacancies in the Apostles and the Fellowship; it is a caricature I’ve both seen written as a homophobic slur, and alternatively heard as a point of some Pride. I doubt there’s much truth in the caricature, and in my view it’s more interesting to think about the class and national backgrounds of those who did and didn’t (Gray Walter, say) get chosen for these prestige positions. But I don’t think it’s entirely irrelevant to finish with a ditty said to have circulated a few years earlier. Andrew Hodges recorded this as oral history in 1983 and did not name his source. My guess would be Richard Braithwaite, himself elected in 1924, and whose own interviews with Laurie Khan about Frank Ramsey reveal him as someone who would have found this amusing in the 1980s:

Turing

Must have been alluring

To get made a don

So early on