On 15th July the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester hosted the Bank of England when they announced the new face on the £50 note. I had got an invitation. not naming the chosen one, and I supposed that MOSI had just rounded up Manchester’s scicomm community. I didn’t think Turing was very likely to be the face — I vaguely expected Dorothy Hodgkin instead. Anyway, Turing it was, which now explains why after years of offering MOSI had finally accepted my offer to do a blog post about Turing in the Science Museum. I believe MOSI when they say they want to continue to use their holdings to tell a diverse range of stories — I for one would like to hear Erinma Ochu’s, without whom the Sunflower project, and the book, would have just been half an idea.

The post is up at the Science Museum in a shorter version. This is the longer original, plus a bit at the bottom about how I offended Simon Singh at the launch. The Science Museum still don’t stock my book in their shop, I have no idea why.

Alan Turing in the Science Museum

Sixty-eight years ago, Alan Turing left Manchester for the summer. As part of his holiday he paid a visit to the Science Museum in South Kensington. For the 1951 Festival of Britain they had agreed to display a new wonder: the Ferranti Mark I, the world's first commercially available electronic computer. But, like most computer installations ever since, it couldn't be made to work in time. So Ferranti created a last-minute replacement, the probably more crowd-pleasing wonder of the Nimrod. Nimrod was the first game with an electronic display, and played a passable version of the matchstick game Nim. When Turing visited, he supposedly managed to both beat Nimrod at its own game, and then to break it, all the while keeping an eye on the attractiveness of the display attendants (he approved).

Dorothy Hodgkin, about 1935. (From IUCr, and probably out of copyright).

Figure 2. Nimrod, the first electronic computer designed for games playing. ©Discovery, March 1951, but current copyright holder unknown.

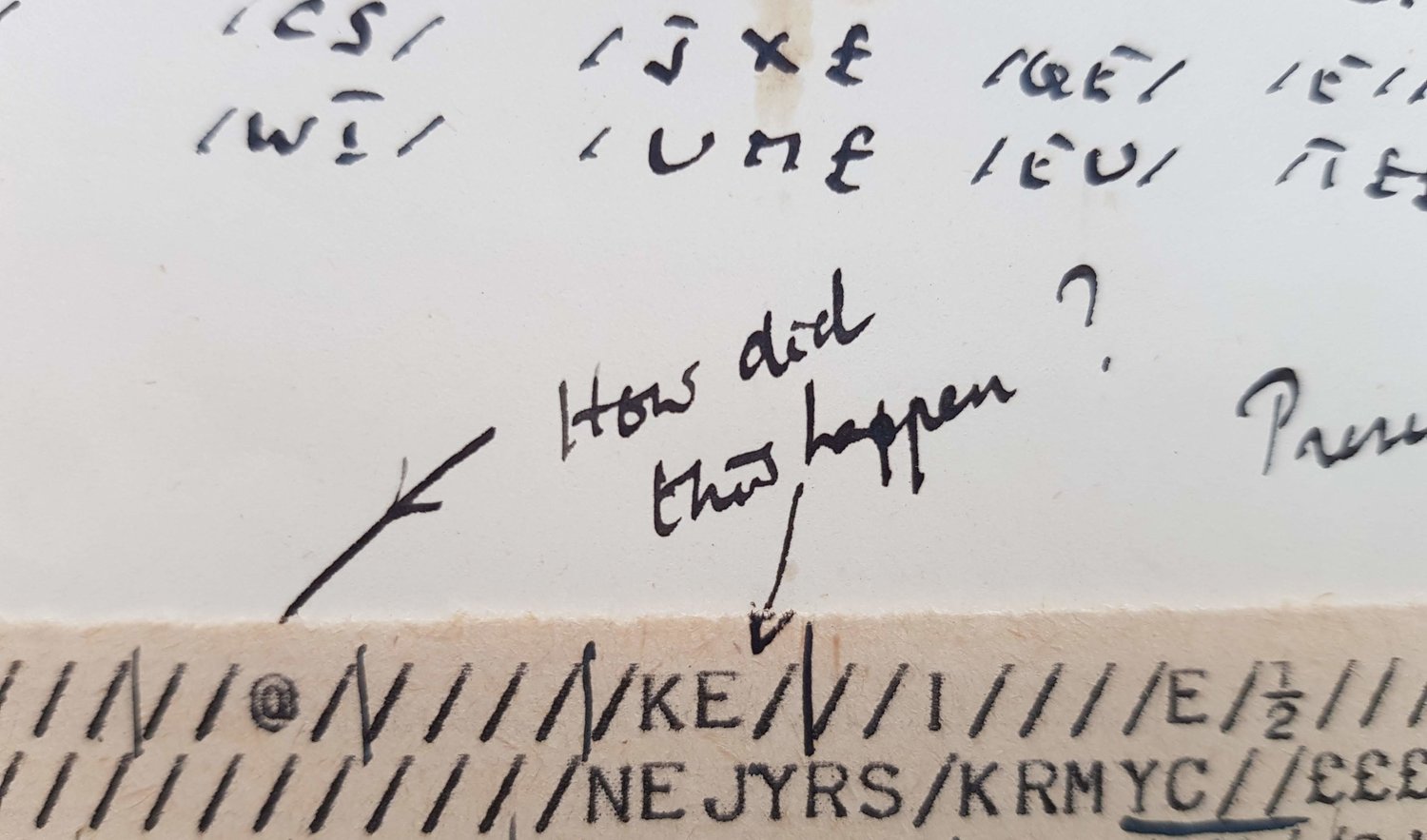

It's no surprise that Turing could hack the Nimrod. His job in Manchester was as the resident, indeed the first, software specialist at the University, and, I discovered in research for my recent book, as a consultant for Nimrod’s maker, the electrical company Ferranti. Nimrod and (eventually) the Mark I, were constructed up the Oldham Road in Moston, so I felt justified in including the Nimrod story in the book, Alan Turing’s Manchester. And it was in MOSI in Manchester, in a windowless basement, that I found a hitherto unknown account confirming the making of Nimrod as a Mark I replacement. That document was part of the vast Ferranti archive that is one of MOSI’s lesser known treasures. The MOSI archive also holds the photographic prints that mark the start of computer marketing. Where today David Bowie or FKA Twigs hunch over their Macbooks in black and white, in 1951 it was Alan Turing, in his role as programming expert, who leaned over the Mark I console to sell the machine of immense, if never quite specified, promise.

Figure 3. Alan Turing (right) and two Ferranti managers in a publicity shot for the new Ferranti Mark I. (c) Ferranti, 1951, but current copyright holder unknown. Copyright claims have been made by the University of Manchester and the Science Museum Group in the past but I doubt these can be for the underlying image.

The Ferranti Mark I was based on a University prototype for which Turing wrote the world’s first, and by common consent worst, programming manual; when Ferranti commercialised the design they had to rewrite the manual more or less from scratch, and so the visitor to the archive can also find the resulting Ferranti manuals, acknowledging the support of ‘Dr A. M. Turing’.

The Science Museum Group’s holdings connect with Turing in other ways too. The various pieces of Douglas Hartree’s differential analyser, and analogue computing device heavily used during the war, attest to the expertise accumulating in Manchester in numerical techniques, that would be crucial in making it one of the two post-war British sites with a computer and attracting Turing to the city. And from those brilliantly ingenious first few years of Manchester electronic computing, led by FC Williams and Tom Kilburn, there’s a surviving CRT tube of the technology that delivered the first practical computer memory, there are a few valves from the Baby that tested it, and an entire logic door from the Ferranti Mark I that commercialised it. But Turing had little direct input in that hardware inventiveness, and by the time the marketing shots had been taken, he was marginalised in the University and disappeared from the Ferranti archive too.

Figure 3. Part of the logic circuitry from the Ferranti Mark I, the world's first commercial electronic computer. (c) Science Museum Group, but used under a free noncommercial license. Believe me this blog is uncommercial.

[MOSI edited the following paragraph out, I imagine for length, in the copy on their blog.]

Turing’s intellectual isolation was made worse by what we now see as his persecution as a sex offender. I couldn’t find much material in the Science Museum Group’s vast holdings to tell much about that story. But there is one object which acquires a sinister cast in the light of Turing’s prosecution for homosexuality, his sentence to a year of chemical castration, and the mixture of defiance and depression that followed. Item A627615 is a set of three ampoules of a form of oestrogen, manufactured by the Dutch company Organon. Scientific isolation of sex hormones in the nineteen thirties had been rapidly followed by this kind of commercialisation. It was a great breakthrough: a reliable supply of these pharmaceutical-grade compounds made cures possible in many areas of medicine, not least Tamoxifen, a life-saving breast cancer drug first isolated in ICI Manchester’s Alderley Park base. But hormone therapy is also how to control sex-drive, and it is likely that Organon’s oestrone was one of the drugs used to enforce Turing’s sentence in the years 1952 and 1953. Without the commercial availability of the drug – and all the marketing pressure that follows – what I wonder would the courts have thought they should be doing with Turing instead?

Jonathan blogs at https://www.manturing.net/manufacturing. Sources can be found in Jonathan’s book Alan Turing’s Manchester, which is available in all good Manchester bookshops except that of the Museum, and can also be bought on online at www.manturing.net. Parts of Douglas Hartree’s Differential Analyser, and the Manchester University and Ferranti computers can be seen in the Science Museum South Kensington, while MOSI continues proudly to host the reconstructed Baby in its entrance hall.

Added on 15th July.

In the Q&A today the guy from the FT asked Mark Carney about whether we were entering a recession, to which the answer unsurprisingly was that the MPC would tell him when they were ready, Inspired by having the actual Chair of the MPC there I used the southern makeup of the nomination committee and Turing’s choice of Manchester as home to ask Carney a question about the relative importance of southern finance and northern industry to the Bank. It is a serious opinion of some serious economists that the British economy is overweight on financial services, and I don’t regret asking Carney about it, even if most of my motivation was to advertise my own presence. (His answer was it was a Bank of the UK, though unsurprisingly he didn’t say we have too many bankers). Later Simon Singh, one of the selection panel, told me afterwards he hadn’t thought my question celebratory enough, and perhaps he was right. I’m certainly sorry if it came over like that. Simon Singh might have been listening out for more pushback about their choice than there actually was: my social media bubble suggests almost everyone thinks he has done a good job , as do I. I think he, the panel, and the Bank of England created a rare bit of inclusive good news today, and along with plugging Alan Turing’s Manchester I tried to get this over in the media work I did with BBC and ITV.

But Dorothy Hodgkin next time, please, though the interests of storytelling ask it be after the JD Bernal papers are unsealed in 2021…